Hot Shots

Friction builds between the district and unvaccinated members of the campus claiming a lack of communication and inconsistencies in the vaccine mandate resolution.

March 12, 2022

It is a relatively universal understanding that when a new law, regulation, ordinance, or policy is adopted, not every person will approve of it. In some cases, it results in tension among the population.

Educational environments are no exception to this reality. The Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community College District is now amid such tension regarding its COVID-19 vaccine mandate resolution.

In November 2021, the district’s Governing Board approved with a six-to-one vote resolution 21-024, better known as the COVID-19 vaccine requirement. Beyond a goal of protecting the public health of the campus community, the resolution was also drafted to help solve issues stemming from “the displacement and exclusion of many students from communities with inadequate access to resources necessary to succeed in distance education.”

However, it appears this exact resolution wound up displacing and excluding many individuals from the campus population.

“It just doesn’t make sense,” said Administrative Assistant Patty Sparks when asked about the administration’s enforcement of the vaccine mandate.

Sparks has worked with the district since 2004 and as of late has been dealing with an ongoing conflict with the employer concerning her unvaccinated status. Sparks emphasized she does not identify herself with the anti-vaccination movement; she said her decision not to get the vaccine came from her faith that she became more involved in after the pandemic had swept through the world. When the vaccines for COVID-19 began rolling out to the public, she said she ended up making her own spiritual and personal decision to not take the shot.

“So I filed a religious exemption and that was granted, but what they didn’t grant was my accommodation,” Sparks explained. “All my accommodation was to continue as I did last semester (Fall 2021) which was to test, mask and obey all the safety protocols within the CDC.”

She is not alone in this experience. A group of close to 20 individuals, including both staff and students claiming to have experienced the same or a similar situation, took to a streetside protest on Feb. 22 to voice their frustrations.

Those present shared experiences mirroring Sparks, describing an exemption with empty accommodations, a fundamental lack of communication, and a feeling of ostracization from the campus.

Michele Clock, the director of Public Information for the Grossmont-Cuyamaca College District, gave an open reply on behalf of the district regarding this issue in an emailed document that opens with this statement: “Protecting the health and safety of our students and employees is our top priority.”

The statement continues: “We contracted with an outside expert to develop a COVID-19 safety plan, in accordance with directives from our Governing Board, as well as local, state and federal agencies.”

In the statement, the district also asserted the exemption process and its enforcement is consistent between both staff and students on campus.

“Human Resources and Health and Safety specialists review the requests. Medical requests had to include verification from treating medical providers, and religious requests had to identify a sincerely held belief. ”

While this all seemed straightforward, as the accommodation process was explained, it grew more complex.

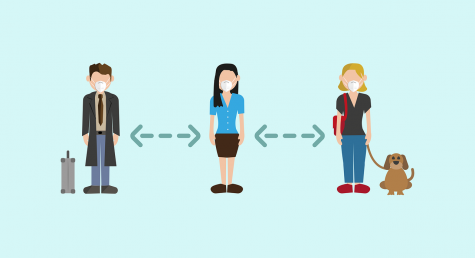

Individuals with exemptions are reviewed as to whether they can be accommodated on campus using a variety of factors. Specifically, regarding faculty and staff positions, locations and functions of a position are considered. The amount of direct contact with others is primarily examined for the general population.

Which means some exempted students are accommodated by continuing their on-campus studies depending on the subject, while others must go through online classes. Exempted employees are accommodated depending on the requirements of their position; otherwise, they were informed to use their leave time as their accommodation.

Segments of this process can sound a bit vague and unclear, mainly in how the district determines who among the exempted are more at risk than others at potentially contracting and spreading COVID-19. It also does not explain why weekly testing is not a secondary option regardless of an exemption.

The administration points to the CDC and WHO, as well as other federal and state agencies as heavy influences in the process for drafting the vaccine mandate resolution. However, it is worth noting while the CDC, WHO, OSHA, and Cal/OSHA all recommend vaccines as a powerful tool against the spread of COVID-19, they do not explicitly state the enforcement of a strict vaccine mandate is required for a safe workplace to be maintained. All of the aforementioned bodies reference frequent COVID-19 testing as an alternative for those who choose to remain unvaccinated.

The district’s choice to use leave time as a form of accommodation has also drawn the ire of these unvaccinated employees.

“That’s taking my property,” Sparks said, echoing others’ sentiments. “I work all year for that paid time away; this is something I have earned and you’re forcing me to give that up.”

It is not certain how this issue will be resolved. With the number of employees requesting exemptions being reportedly low – only 88 of 2,417 total employees according to the district’s numbers – there is likely little incentive to do much.

This puts people in Sparks’ position in a bind. When asked about her options, she replied: “None, they are making me use my vacation time. I have about five weeks of vacation after that unpaid vacation, and on June 30, I start discipline which pretty much means termination.”

Some employees have opted for the route of early retirement; others have begun searching for options with other employers they hope have accommodations better suited to their needs.

Although this has not discouraged the members of this group from putting continued pressure on the district to provide them with better information and to change the resolution to allow them back on campus. The common question they seem to ask is: Why can I not return to campus if I am willing to submit to weekly COVID tests and follow other recommended health and safety guidelines such as masking and social distancing?

In Clock’s statement, the district maintains it is “focused on educating and communicating with our campus community on COVID-19,” by sharing this information through the district’s websites, emails and open conversations.

The statement ended with this assurance: “We are constantly monitoring the public health situation.”

Both sides are staunch in their positions, and communication between the groups seems unsuccessful. With uncertainty shrouding this affair, it is unclear when or if a solution will be reached soon.

This article originally appeared in the March 2022 print issue of The Summit.